|

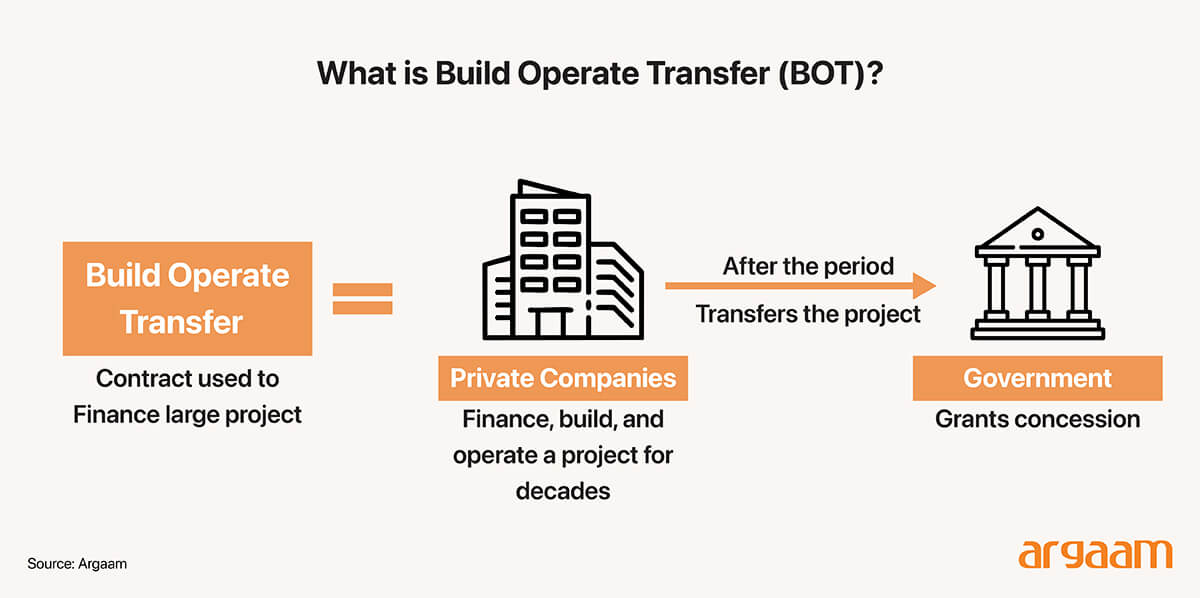

The increasing global shift towards infrastructure privatization presents significant investment opportunities for sovereign wealth funds and institutional investors seeking stable, long-term returns. Saudi Arabia, leveraging its substantial capital reserves and strategic economic diversification goals under Vision 2030, is well positioned to consider bidding for operating rights of major highways, crossings and iconic bridges in countries like the UK, and Turkey. On September 8, Turkey announced a multibillion-dollar plan to sell the operating rights to two iconic Istanbul bridges and a series of highways, potentially the biggest privatization deal in the country’s history. The UK’s highways network remains a compelling investment opportunity for Saudi investors, particularly should the government decide to revisit the privatisation or commercialisation of motorway and major road operating rights in the future. Till today, the operating rights of only one highway in the UK is privatised, which’s the M6 highway in the West Midlands. These assets, characterized by high traffic volumes comprising tens of thousands of diverse vehicles daily, offer a compelling proposition in terms of predictable cash flows, revenue generation, and portfolio diversification. The acquisition of operating rights through Transfer of Operating Rights (TOR) models enable investors to capitalize on existing infrastructure without the capital-intensive burden of initial construction. But even if it’s a Build-Operate-Transfer or Design-Build-Finance-Operate models, the Saudi investor still stands a lucrative Return on Investment as we will demonstrate through our financial analysis later in the article.  Projected 5.17% ROI in just one crossing A comprehensive study by the UK-based Institute of Economic Affairs can provide useful insights into the UK case in particular as it analysed pilot schemes envisaged models of concession-based and tolling arrangements with meaningful private sector stakeholding. Though the UK government hasn’t yet decided on whether it starts inviding bidders for the operating rights of some of its major crossings and highways, the study demonstrates strong economic rationale and promising financial returns if the UK government decided to privatise its massive network of roads. A Saudi investor winning the operating rights of the Dartford Crossing, one of the busiest river crossings in the UK with approximately 160,000 vehicles crossing daily, could expect a lucrative financial return. The Crossing is currently the only way to cross the Thames east of London by road and links the counties of Essex and Kent via the cable-stayed, 137 metre high Queen Elizabeth II bridge for southbound traffic and two 0.8 mile long tunnels for northbound journeys. Based on up-to-date UK government data, a typical daily traffic in the crossing is %42 goods vehicles and while cars and other vehicles make up %58, and given that the total number of daily crossings is 160,000 vehicles, the daily average toll revenue can be estimated by applying the specified government toll charges. Specifically, goods vehicles are charged £4.20 each, while other vehicles are charged £3.50 each.

The total revenue could be a daily yield of approximately £607,040. This means that the annual revenue from a single crossing like Dartford could be in the region of £221.6 million. Accounting for operating and maintenance costs, which’s typically around 30% suggests annual operating expenses near £66.4 million, leading to a net operating income of approximately £155 million per year. If a thirty-year Design-Build-Finance-Operate contract for a highway scheme similar to those offered between 1994 and 1997 in the UK were awarded in 2025, the original investment of approximately £1.1 billion would need to be adjusted to account for nearly three decades of inflation. Construction, financing, operation, and maintenance costs have all increased over time due to rising material and labor expenses and changes in borrowing costs. Taking inflation into consideration, the original £1.1 billion investment figure from the 1990s could roughly triple in nominal terms by 2025, potentially reaching around £3 billion or more today. So to calculate the Return of Investment (the outcome of the division of the net operating income and the initial investment capital multipled by 100), will be around %5.17 annually. Calculating the Net Present Value isn’t feasible since the discount rate used to convert future cash flows to present value is subject to variation over time due to changes in interest rates. For example, the UK inflation is projected to decline to 2% in 2027 against today’s rate of %3.8 at the time of writing this analysis on September 17, 2025.

A lesson from Turkey: Key Metrics Driving Success in Infrastructure Operating Rights Investor success in buying the operating rights of a highway or a crossing or a bridge, however, hinges on meticulous due diligence, including rigorous analysis of two key infrastructure planning metrics. a) origin–destination matrices b) willingness-to-pay surveys An academic paper published in 2018 and titled "The Privatization of Roads: An Overview of the Turkish Case" offers valuable insights, particularly highlighting how previous experiences in Turkey revealed the consequences of neglecting critical metrics during the sale of operating rights. The analysis focuses particularly on major BOT projects such as the Gebze-Orhangazi-İzmir Motorway, Izmit Bay Bridge, the Istanbul Strait Road Tube Crossing Project (Eurasia Tunnel), and the Northern Marmara Motorway including the Third Bosporus Bridge. These projects collectively represented massive investments exceeding $10 billion and served strategically important routes with high expected traffic volumes. A critical financial issue for these projects has been the inaccurate traffic forecasts and demand risk management prior to privatization, since The Turkish authorities did not conduct detailed and precise origin–destination matrices. Origin–destination matrices are data tools used in transportation planning to represent the number of trips between various origins and destinations within a region during a specific time period. Essentially, an O-D matrix shows how many travelers start from each origin area and end in each destination area, providing detailed insights into travel demand and patterns. They haven’t also conducted surveys assessing the willingness to pay by road users, which are essential for reliable demand estimation. For example, the toll for the Eurasia Tunnel was set at $4 USD plus 18% VAT (approximately $4.72), which is about 188% higher than the current tolls of the Bosporus and Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridges (approximately $1.63). Since the toll will be collected in both directions for the tunnel (unlike one direction for the bridges), the effective round-trip toll becomes approximately 477% higher, making it unattractive for use. These BOT projects in Turkey had to compete with free alternative routes, making users highly sensitive to toll levels. For instance, tolls at the Eurasia Tunnel were set at nearly 188% higher than those at the existing Bosporus bridges, which discouraged usage and constrained traffic growth projections. When the actual traffic fell short of guarantees, public agencies faced substantial financial liabilities, and private operators struggled to generate expected returns. For example, the traffic guarantee for the two ongoing Istanbul Strait projects targeted capturing almost 49% to 82% of total traffic based on outdated traffic statistics, which did not realistically account for the higher toll levels and competing infrastructure. Such overestimation directly impacted the projects’ financial viability, increasing risks for both public and private stakeholders. Careful project selection, comprehensive demand assessment, and prudent financial structuring are paramount to maximize returns and secure long-term value creation in this dynamic sector. |

|

|

|

|

|